In his seminal 1977 Science magazine article, “The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine,”1 Dr. George Engel outlined the limitations of the biomedical model and proposed a new model which he termed the biopsychosocial model. The biopsychosocial approach systematically considers biological, psychological, and social factors and their complex interactions in understanding health, illness, and healthcare delivery.

In many ways, this approach sounds so intuitive and obvious but when it was introduced, critics asserted that “the physician should not be saddled with the problems that have arisen from the abdication of the theologian and the philosopher.” Another called for the “disentanglement of the organic elements of disease from the psychosocial elements of human malfunctions.”1 In spite of these reservations, the biopsychosocial model continues to play a central role in medical school curricula and continues to provide the theoretical underpinning for whole person and patient centered practice.

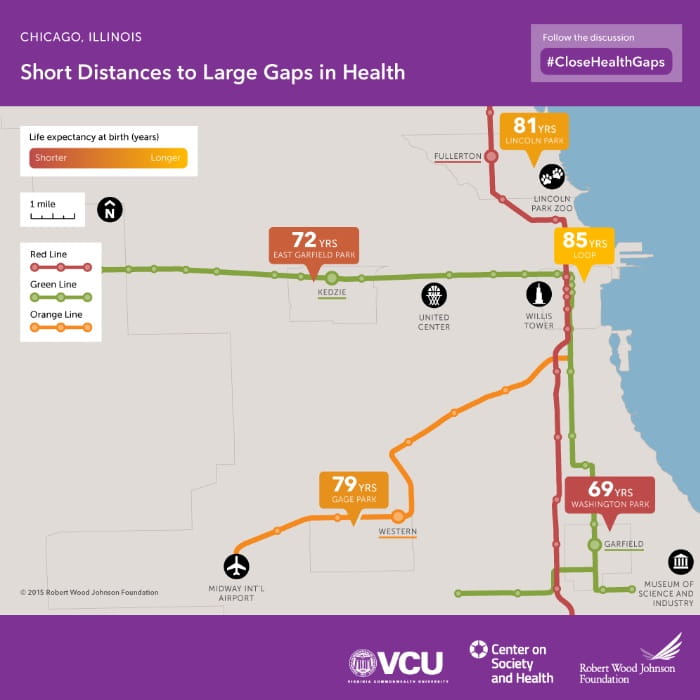

In recent years, there has been increased focus on the impact that social determinants have on health outcomes. This focus has mirrored the advent of population health as a discipline and has also been facilitated to a large extent by the availability of data and analytics that support robust outcome measurement at both the population and individual patient levels. Forty-one years after Dr. Engel introduced the biopsychosocial model, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published a position paper2 in which it acknowledges the role that social determinants of health play in a person's overall health and health outcomes. There is irrefutable evidence that where a person is born and the social conditions they are born into can affect their risk factors for premature death and their life expectancy. A Virginia Commonwealth University study in 20153 showed that babies born just a few stops away on the subway’s Green Line in Chicago face up to a staggering 16-year difference in life expectancy.

An analysis of studies measuring adult deaths attributable to social factors found that in 2000, approximately 245,000 deaths were attributable to low education; 176,000 were due to racial segregation; 162,000 were due to low social support; 133,000 were due to individual-level poverty; and 119,000 were due to income inequality. The number of annual deaths attributable to low social support was similar to the number of deaths from lung cancer (n = 155,521)4. These sobering statistics are impacted by factors such as environmental conditions, housing, transportation, access to food and healthy food, the digital divide and racial and ethnic disparities.

It is the widespread availability of this information that will ultimately facilitate the development of interventions and programs that will help mitigate the deleterious effects of these socioeconomic factors. Much of this work will require deep collaboration across multiple entities, federal and state goverments, community resources, social services and healthcare delivery systems.

Four decades after Dr. Engel described the biopsychosocial model, many of his students are still working to implement it fully; he would be proud of these efforts.

1https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/MediaLibraries/URMCMedia/medical-humanities/documents/Engle-Challenge-to-Biomedicine-Biopsychosicial-Model.pdf

2https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M17-2441

3https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/articles-and-news/2015/09/city-maps.html

4https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3134519/

5https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2751390?utm_source=silverchair&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=article_alert-jamanetworkopen&utm_content=wklyforyou&utm_term=091819&stream=top

Meet NextGen Ambient Assist, your new AI ally that generates a structured SOAP note in seconds from listening to the natural patient/provider conversation.

Read Now